*This introductory note is a translation of a brief article originally published in Greek for Skenè: Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies, Vol.12. It can be accessed here.

Abstract

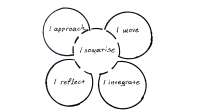

Using as a point of departure an indicative illustration on key steps of the practice, this brief article introduces the reader to the methodology of Somatic Acting Process®. It aims at outlining a revisited perspective on somaticity through movement-based actor training and somatics. The somatic methodology at the core of this note brings into dynamic interrelation actor movement education, the rehearsal process and academic research. More specifically, it emerges from the critical integration of the embodiment process in Body-Mind Centering® (BMC®) by Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen and Robin Nelson’s Practice-as-Research (PaR) academic model. The way in which this new methodology reviews logocentric elements in theatre praxis and proposes the perception of each actor’s “somatic logos”, is offered as an experiential invitation to each reader through the basic steps of the process.

Key words

somatic methodology, acting-movement, somatics, Practice as Research, somatic logos

The above illustration puts in shape the basic experiential steps of the methodology I introduce as the ground of the acting approach Somatic Acting Process®.[1] They underlie my teaching to actors in training, focusing on their movement-based expression, the way I develop or support the rehearsal process as director/movement director and my academic research as practitioner-researcher. Before I return to a summary on the content of the image within this introductory note, I wish to clarify how I approach the experiential notion of somaticity in acting. Influenced by a specific group of movement practices called somatics,[2] including Alexander Technique and the Feldenkrais Method, I revisit the word soma (body in Greek) and relevant vocabulary in a way that refers not only to physical but also to internal and dynamic manifestations of bodies in acting. Towards this conceptual modification from within somatics, I have been inspired by the American philosopher and movement practitioner Thomas Hanna. Hanna reintroduced the Greek word soma in order to highlight the significance of the experiential and holistic body in comparison to the body as object.[3]

I further develop this conceptual revision in my practice adding the need to recognise somatic difference within the diverse coexistence in-between actors-educators-directors/movement directors. To this end, I bring into relation interactive methods from Body-Mind Centering® (BMC®) and Authentic Movement as contemporary somatic practices and theories of embodied intersubjectivity.[4] My aim is to review logocentric problematics in educational and artistic processes with particular emphasis on the hegemony of text, language and cognitive analysis as a primary or unified perception. More specifically, for the “map” of my methodology (see the illustration above) I have been inspired by the dynamic dialogue between Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen’s embodiment process in BMC®[5] and Robin Nelson’s academic model of Practice as Research (PaR) or praxis as “theory imbricated within practice”.[6] Each step of the process reflects the individual actor’s, educator’s or director’s/movement-director’s first-person and present experience within the innate co-presence of educational and creative processes in theatre. The steps do not follow a specific hierarchy but aim at inspiring a continuous flow of dynamic connection between movement, language and perception that has each actor's somaticity at its core. In brief, the following steps come up when, for instance, the actors work with dramatic text:[7]

I approach: depending on the type of the dramatic text, I formulate the first contact with the work as a physical “guide”. If the text follows a narrative structure, I read the evolution of its flow as a story. Instead of starting with a form of cognitive analysis, I initially focus on elements such as certain somatic actions and relationships between dramatic roles (if any). Alongside, I activate my imagination by framing images and metaphors that are either in the playtext or accompany the reading experience.

I move: I explore the first “meeting” between my kinesthetic perception and the dramatic text as a creative “guide”, recognising that an external source meets my personal and interpersonal experience. I can focus on the whole play, the developmental arc of a role or on specific scenes. In this step I use as a kinesiological “map” the experiential anatomy of different systems, such as skeleton, muscles and organs, and developmental movement patterns such as relationships between movement expression and various breathing methods. For instance, how does the movement of my skeleton and joint articulation support the physical structure and articulation of a role? How can the experiential connection between my lung breathing and “cellular breathing” as a whole-body movement support the vocal and language perception of the text?

I somatise: in this step, I make the transition from the kinesthetic exploration to the somatisation of my study. I recognise I move into somatisation when I do not feel the distance between the text as external “guide” and the internal experience that emerges with the development of my physicality. The technical structures begin to release into improvisation. This release does not mean absence of structure, since I need to maintain the awareness of the development of my physical expression. Yet, the structures are now more “fluid”.

I reflect: I bring into my attention the elements that came up during the previous steps. What did I discover? What helped me? What would I like to explore further towards the evolution of the process? What new knowledge emerges if I return to the dramatic text based on my empirical study? Ideally, in this step it becomes clear that there is no gap between my cognitive and kinesthetic experience. In the process of practice research this is also the step during which interaction with complementary theoretical ideas can come up. The term I introduce in order to emphasise this understanding of each actor’s logos not only as cognitive and verbal but also as somatic, dynamic and multiple experience is the concept of “somatic logos”.[8] The notion is influenced by ideas of Maurice Merleau-Ponty in the field of phenomenology and more specifically it was inspired by the analysis of logos as embodied “flesh” in his theories.[9]

I integrate: I complete a cycle of this process by getting the opportunity to connect my findings in such a way that allows me to put together choices towards the staging of a scene and the embodiment of a role or setting up the ground for the next study/rehearsal. Integrating does not mean finalising but embodying the awareness of creation as a dynamic process, either in training or in the rehearsal process.

Bringing this note into a closure, I would like to invite each one of you as reader to explore the above steps as you understand them through the offered brief practice outline. The point is that the given methodology finds substance only through personal experience. You could replace the dramatic text with any inspirational “guide” such as a poem, a song or an image to express and integrate your own somatic logos.

[1] The formal shaping of this practice began as part of my doctoral research with the support of a full-time scholarship from the Greek State Scholarships Foundation (IKY) and an Elsie Fogerty Research Degree Studentship from the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama (see Christina Kapadocha, «Being an Actor/Βecoming a Trainer: The Embodied Logos of Intersubjective Experience in a Somatic Acting Process», PhD Thesis, Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London 2016).

[2] See Martha Eddy, Mindful Movement: The Evolution of the Somatic Arts and Conscious Action, Intellect Ltd., Wilmington 2016.

[3] Thomas Hanna, Bodies in Revolt: A Primer in Somatic Thinking, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York 1970, p. 35.

[4] On how, for instance, I interconnect Authentic Movement and theories of intersubjective psychoanalysis in the acting process and as an actress-researcher see Christina Kapadocha (2018), “Towards Witnessed Thirdness in Actor Training and Performance”, Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, 9:2, pp. 203-216.

[5] Bonnie Cohen-Bainbridge (2012), Sensing, Feeling, and Action: The Experiential Anatomy of Body-Mind Centering, Contact Editions, Northampton 2012, p. 157.

[6] Robin Nelson (2013), Practice as Research in the Arts: Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York, p. 16.

[7] Parallels can be drawn with how Jean Benedetti outlines the six principal processes of an actor’s work on a role according to Konstantin Stanislavski (see Jean Benedetti, Stanislavski: An Introduction, Menthuen Drama, London 2008, p. 41).

[8] In my doctoral dissertation the term started as “embodied logos”. I analyse its further development into “somatic logos” in the chapter “Somatic Logos in Physiovocal Actor Training and Beyond” of the edited collection Somatic Voices in Performance Research and Beyond, as part of the Routledge Voice Studies series (London 2021, pp. 155-168). You can find more about the Somatic Voices project as a whole and the book here.

[9] See Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, trans. Αlphonso Lingis, Northwestern University Press, Evanston 1968.

References

Benedetti Jean, Stanislavski: An Introduction, Menthuen Drama, London 2008.

Cohen-Bainbridge Bonnie, Sensing, Feeling, and Action: The Experiential Anatomy of Body-Mind Centering, Contact Editions, Northampton 2012.

Eddy Martha, Mindful Movement: The Evolution of the Somatic Arts and Conscious Action, Intellect Ltd., Wilmington 2016.

Hanna Thomas, Bodies in Revolt: A Primer in Somatic Thinking, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York 1970.

Kapadocha Christina, “Being an Actor/Becoming a Trainer: The Embodied Logos of Intersubjective Experience in a Somatic Acting Process”, PhD Thesis, Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London 2016.

______, “Towards Witnessed Thirdness in Actor Training and Performance”, Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, 9: 2 (2018), pp. 203-216.

______, “Somatic Logos in Physiovocal Actor Training and Beyond”, In: Christina Kapadocha (ed.), Somatic Voices in Performance Research and Beyond, Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon 2021, pp. 155-168.

Merleau-Ponty Maurice, The Visible and the Invisible, trans. Αlphonso Lingis, Northwestern University Press, Evanston 1968.

Nelson Robin, Practice as Research in the Arts: Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances, Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York 2013.